Black Hills Raptor Center

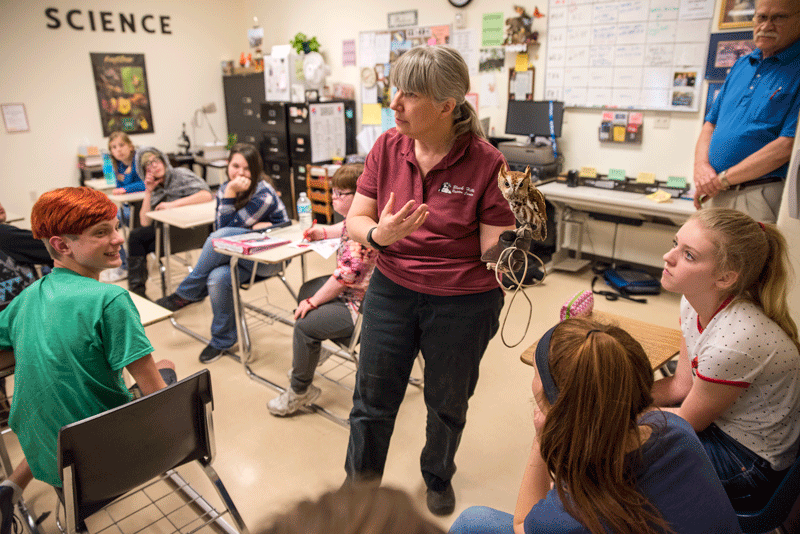

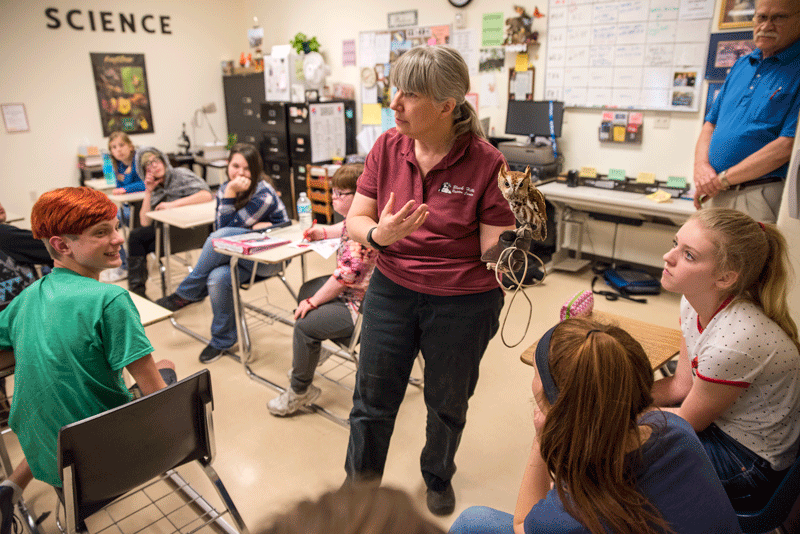

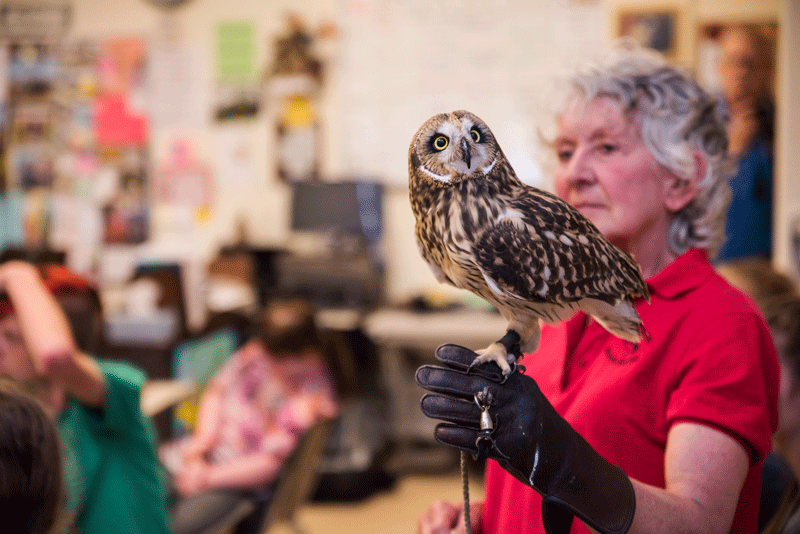

The Black Hills Raptor Center is a non-profit organization that combats “nature deficit disorder” in area residents. The Center relies on its best ambassadors—two Eastern Screech Owls, a Red-tailed Hawk, a Short-eared Owl, an American Kestrel, and a Ferruginous Hawk, all unable to live successfully in the wild—to increase awareness of wildlife conservation.

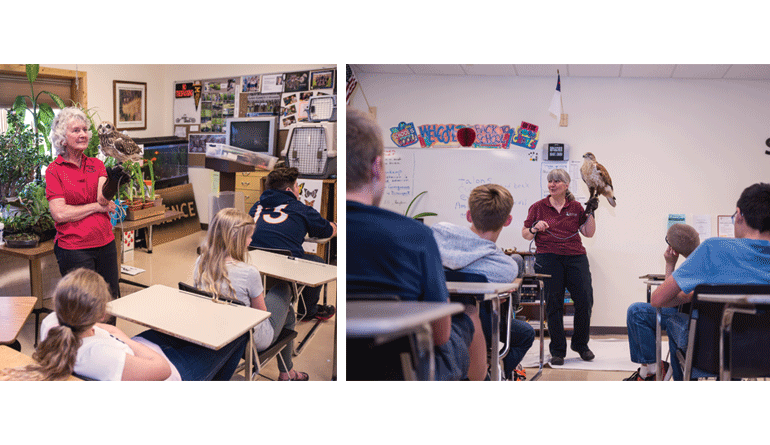

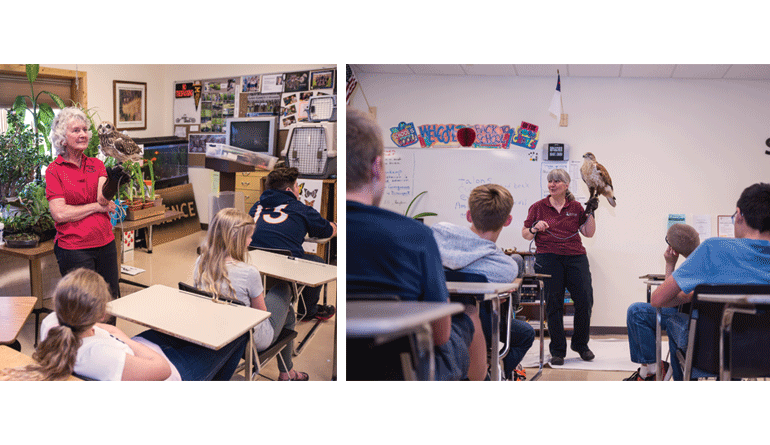

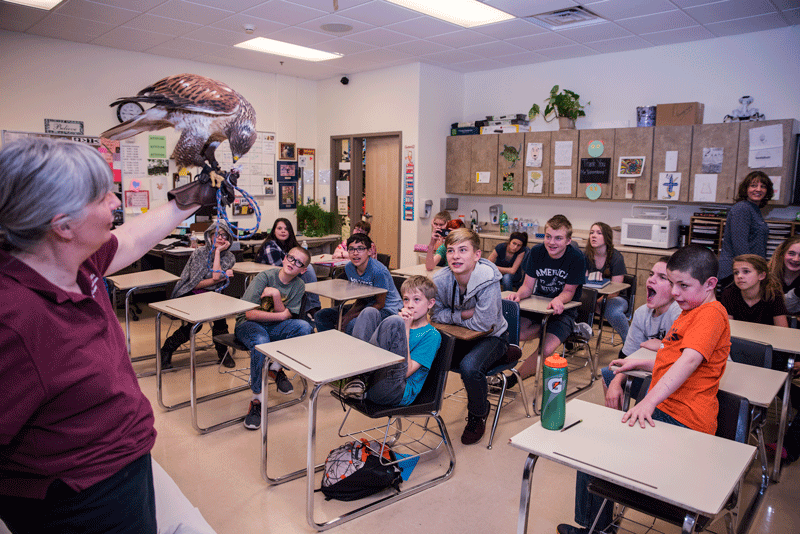

For a nominal fee, anyone can request an educational program through the Black Hills Raptor Center’s website. The birds and their handlers share the uniqueness, adaptations, and habits of raptors through interactive, hands-on, age-appropriate programs. The birds can visit children’s birthday parties, classrooms, or even private dinner soirées—they recently did a program at a wedding!—where guests have the chance to develop a powerful emotional connection to the center’s awe-inspiring tenants.

At the 125 to 150 “up-close-and-personal” educational experiences that the center delivers per year, the birds never fail to generate questions among onlookers. People become more and more curious about the types of raptors that live here, their habitats, their needs, and their vulnerabilities. These magnificent creatures also help Maggie and her team of volunteers to share the Black Hills Raptor Center’s core message: that every decision we humans make has a far-reaching impact. The staff want to help both children and adults to make positive ones.

The facility is part of what co-founder and president Maggie Engler has dreamed of since she was a child—a nature center where she could help educate and inspire the public to care for wildlife and our planet. After college, Maggie worked in conservation and fundraising for more than two decades before finally joining her friend John Halverson to develop an organization that would fulfill her dream. In 2010 the plan came to life and the Black Hills Raptor Center was born. “Or hatched,” Maggie quips with a smile.

“All of our programs have a conservation message,” she explains. “From composting and green building to growing our own food and recycling. If everybody does one small thing, it adds up to big things. We want to help people understand that these animals have a place in the world—and that their success is directly linked to the survival of us all.”

New Complex Underway

Until now, the Raptor Center’s staff could not treat injured birds on site or on location where Black Hills residents might have discovered them—perhaps after hitting a building, or becoming caught in a fence. Partner veterinarians have helped save birds for rehabilitation at the Center—but those days are over.

A full-blow rehabilitation and education complex is in development for five acres just east of the Rapid City Airport. The new facility will house 15 individual “mews,” or large homes, for permanent-resident birds who will be able to participate in education programs. Along with a rehabilitation facility, veterinary office, and an on-site home for the facility’s care taker, the complex will finally be everything Maggie dreamed of all those years ago—a place to care for our precious wild creatures, and inspire the public to care for their world.

Fun Facts

- 22 volunteers

- 235 birds have been provided with supportive care

- $3303 spent on mice and rats as bird food

- 72 birds have been transported to other rehabilitation centers for treatment

- 140,545 people reached since 2012

- 719 educational programs since 2012

What to do with an injured bird:

- Assess the situation from a distance. Close contact with humans can be very stressful for wild animals. First use binoculars or a camera’s zoom lens.

- Contact the SD Department of Game Fish and Parks (find the closest officer here), the Black Hills Raptor Center (605.381.9707), or a local humane society for instructions.

- If you are advised or must move a raptor, then wrap it in a towel or blanket that covers the head. Stay away from the bird’s feet, the most dangerous part of a wild bird. If you have a box or other safe container, then use it! Keep your vehicle as quiet as possible as you transport the bird. Loud noises can stress animals further.

- While attempting to help, you are protected by Good Samaritan laws, but it is against the law to keep a wild animal more than 24 hours without a rehabilitation permit. Contact authorities right away.

Written by Jaclyn Lanae

Photos by Jesse Brown Nelson